Here’s something I find fascinating about horror movie fandom: Halloween II – the 2009 sequel to Rob Zombie’s remake of Halloween, which is decidedly NOT a remake of the 1981 film of the same name and makes a major note out of that – has quite the contingent. I don’t know if there’s anybody who identifies exclusively as fan of the franchise that considers the movie to be the best Halloween entry since the 1978 original, but there are definitely Rob Zombie fans who consider it to be so. On top of that, there are Zombie fans who consider it to be the outright best of the franchise OVER the original. And on top of THAT, there are Zombie fans who consider it to be out-and-out his masterpiece. And mind you, all of these superlatives appear to be unanimously contingent on the film’s director’s cut that released on home video.

I have another superlative to consider with regards to Halloween II without the scruples those other three bring out of me: Rob Zombie’s Halloween films are fundamentally his epic and Halloween II is as critical to that collective qualification in the way that Francis Ford Coppola’s The Godfather Part II gives The Godfather‘s full story an operatic scope and weight. Zombie’s Halloween films each had the same budget – $15 million, which would be the largest budget he’d work with as of 2022 – but the remake was the sort of thing he had to get out of the way in order to dig into what about this material REALLY fascinated him. Halloween ’07 was a small scale-story of Michael Myers, but Halloween II expands that canvas to a variety of approaches both familiar to Zombie (as in a roaming travelogue reflecting on America’s curdled soul a la The Devil’s Rejects, my pick for Zombie’s best film) and forward-looking (as the psychological and hallucinatory elements would foresee The Lords of Salem, my favorite Zombie film).

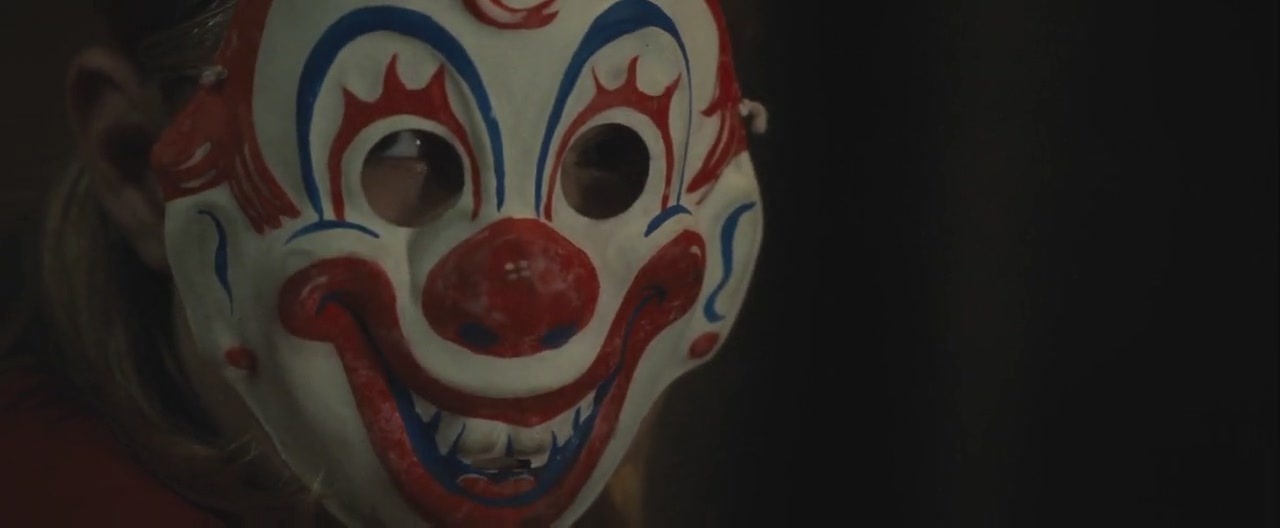

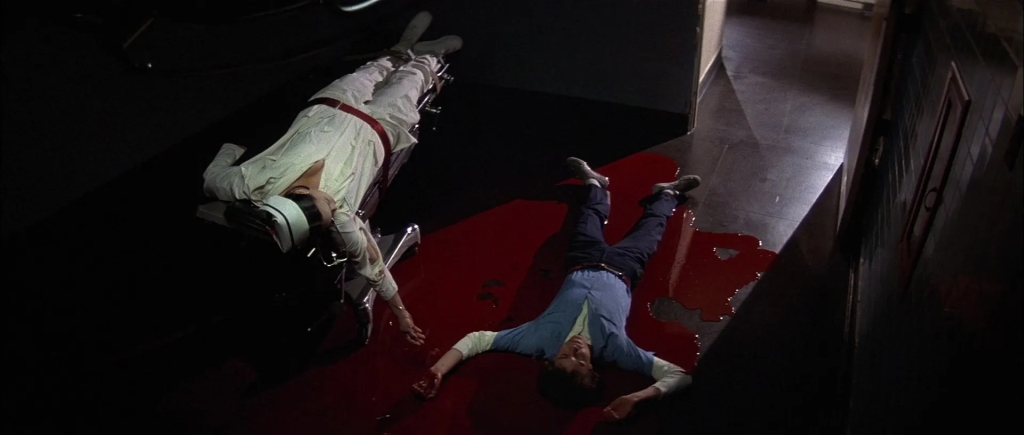

Before either of those things, we are however treated with a note-perfect slasher mini-movie that IS sort of a remake of Rosenthal’s 1981 follow-up as it follows Laurie Strode (Scout Taylor-Compton), the final girl to Michael’s sudden rampage in the first movie. Hours after she shot her assailant (Tyler Mane, with flashbacks to him as a child now performed by Chase Wright Vanick as Daeg Faerch had matured too quickly in the 2 years between these movies), she’s admitted into Haddonfield’s local hospital in a disorienting sequence of frenzied first responders moving bodies through halls and cutting into open wounds and physical trauma with horribly microscopic shots of bloodied instruments and flesh being opened and closed all over, a clinical context of the sort of brutality slasher films traffic in. One of the ambulances is on its way to the morgue with Michael’s body bag in tow, but somehow a disastrous crash is enough to wake him from death itself so he can walk down a foggy rural road to a destination that’s kept ambiguous enough for the following scenes to maintain a brilliant contextualization gambit that I’ll say no more on. Best to keep it fresh for anyone who has not had the privilege of watching Zombie’s Halloween II yet.

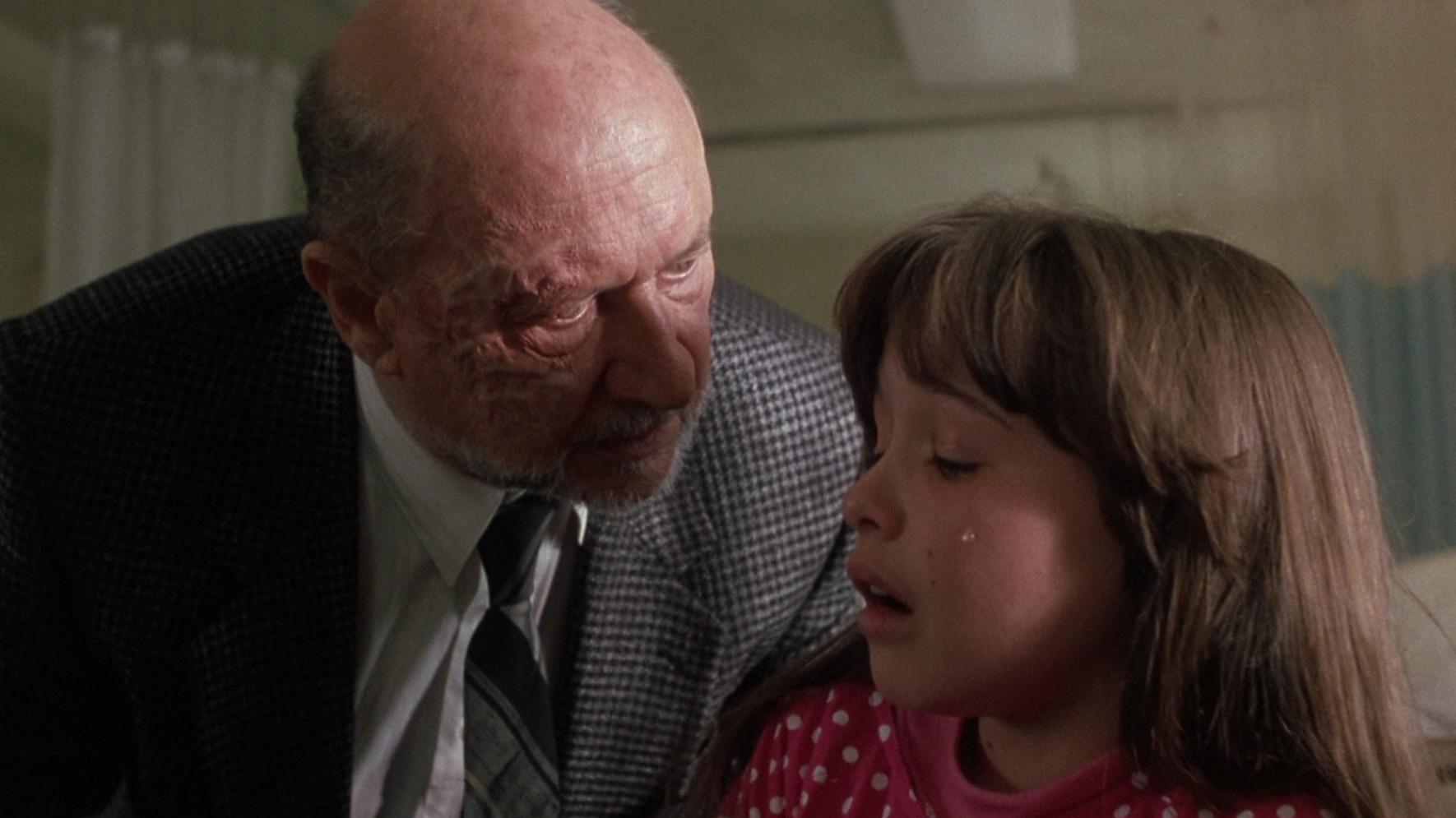

When the film proper begins though, we are treated with three different plots to follow: Most critical of these is Laurie in the aftermath of that shocking event now living in the care of Sheriff Leigh Brackett (Brad Dourif) and her best friend Annie (Danielle Harris), who turned out to survive her encounter with Michael. Despite her certainty that Michael is dead, Laurie’s still struggling with the psychologically scars of his actions. Michael, in his own storyline, has become a drifter since being rejected by Laurie, his unsuspecting and quietly beloved baby sister. But Laurie’s about to get hit with that fact as Dr. Sam Loomis (Malcolm McDowell), a fellow survivor of that violence and Michael’s former psychiatrist in the 15 years between his first and second set of murders in Haddonfield, has published a sensationalist tell-all true crime book of the full Myers affair and is touring that novel as a publicity-seeking primadonna, a rock star approach to hiding his own pain and guilt. Needless to say, they are all connected by that favorite theme of recent horror cinema: trauma and trying to explore that Laurie (and Annie, though she’s not in focus as much), Michael, and Loomis all came away from that awful Halloween night with deep wounds that they simply don’t know how to close. Which is something I find equal parts ambitious in its scale and generous in its sympathy.

The results of this three-way split vary: Loomis’ material is outright godawful, maybe my least favorite thing in any of Zombie’s movies with its shrill attempts at celebrity satire, and mostly responsible for why I’m not on the raves for this. But Laurie and Michael’s are obviously the parts that inspired Zombie most, as Michael’s functions as the surveying long walking journey I mentioned resembling The Devil’s Rejects‘ unspoken cynicism about America and both storylines find pockets in which to shovel in the most macabre autumnal imagery to dreamily project the damage in these characters onto the viewer. These images – cut with awe-struck focus by Glenn Garland and Joel Pashby while often featuring Sheri Moon Zombie returning as Deborah Myers – invoke the festive ghoulishness of Halloween or the ephemeral ghostly textures of black-and-white on film, particularly when it comes to a mental breakdown Laurie has at the trashiest Halloween barnhouse party. They also weaponize what Zombie and cinematographer Brandon Trost have put together as my single favorite depiction of Illinois in late October in this franchise and the closest I think they ever got: Michael’s journey normally takes place at night within the sad blues given depth by fog and field stalks that cover him while Laurie’s daytime life ends up dressed in the miserable grays of the sky against falling arbor reds that stress how much everything is dying and how that dying infects the soul of these characters. I especially enjoy the weird rural Midwest isolation that the Brackett home has, nothing there but a house and a single leafless tree.

13 years ago when I first watched this, I would have considered the slasher genre a poor context for which to try to unite melancholy on both killer and survivor but I guess re-visiting this and especially being exposed to the Director’s Cut have allowed me to open up what it wants to communicate: it fucking sucks being a character in a slasher movie, whether Final Girl or Slasher or in between. Your fate is set and any control you could have is lost before you realized it. Halloween II‘s not necessarily as self-referential as that sounds, but what’s impressive is how it doesn’t approach the matter in a way that postures at having any of the answers to dealing with these issues, it merely wants to explore and empathize with the difficulty without didactism or exploitation. By the time Michael reaches Haddonfield, there is no “that’s so cool” vibe about the grindhouse aesthetic like Zombie usually transparently wears in his film projects nor is there very much blood in the movie at all outside of its opening hospital sequence. The most heartbreaking kill happens entirely off-screen and we are forced to watch more than one character in separate scenes collapse in reaction to finding the corpse (and the director’s cut takes this even further by intercutting home video footage of the actor as a child).

Anyway, I may as well dig up the lede I’ve buried: a lot of this effect that Halloween II has is so much stronger in that Director’s Cut that everyone raves about than in the Theatrical Cut, although I do admire both versions. The majority of the added or re-arranged material is on the Laurie storyline which intensifies just how devastating it is when your mind and emotions have not healed at the same rate as your body: the theatrical cut postures these events as taking place a year after Halloween ’07, but the director’s cut pushes it further back 2 years to add more frustration. The extended material deepens the relationship between Laurie and Annie in particular to a disconsolate breakdown of what we once saw as a loving friendship: Laurie is constantly antagonistic and lashing out at Annie, who is tired of maternally holding her friend’s hand and appears to have an unspoken tendency to trap herself in her home, added further by the extensive scarring we can see on Annie’s face lest we forget that Annie’s the one who was stabbed and mutilated (in the meantime, Dourif’s Brackett is so on the outside of this conflict that he’s not even aware of how often he ends up mediator when he’s able to reach out to Laurie just by eating pizza weird). There’s further stretching out of Laurie’s angrier sessions with her patient therapist (the late Margot Kidder, who was herself no stranger to battling trauma and mental illness) that now mirrors Michael’s own sessions with Loomis in the first picture. Probably the most upsetting addition for me is a sequence of Laurie walking down the street, finding a petting zoo, and smiling as she meets a baby piglet that’s totally benign and ostensibly a rare moment of respite for her in this psychiatric maelstrom, but cross-cut in the director’s cut with a distressed therapy session to re-contextualize this as one of her worst triggers and destroying any sense of warmth that such an activity could associate with.

Laurie in the theatrical cut is staying above water but watching the level rise, Laurie in the director’s cut is already losing breath and watching the surface get farther and farther above her. This makes all the difference when it comes to the density and thickness of Halloween II‘s moodiness, earning the hopeless manic tragedy of its climax and particularly the director’s cut ending. It also just gives deeper framing to Michael’s own resignation to his inhumane beastliness (a theatrical cut sequence where a child innocently encounters him and asks if he’s a giant a la Ghost of Frankenstein is beat at its potency by a moment where Michael encounters a roadside billboard of Loomis’ book and stares at it with the saddest eyes through his hood and decaying mask, even in spite of the scene being juxtaposed by the editing with my least favorite moment in both cuts) and Loomis’ pathetic inability to even acknowledge his injury as anything except a means to capitalize.

Halloween II IS in the end a messy imbalanced movie by any cut, but it is sincerely dealing with unwieldy topics and portraying with critical honesty our improper equipment to tackle those topics: us being horror cinema, us being the United States, and us being the people who do have to live with that trauma in different sorts. By that effect, it’s a heavy movie because of the sobriety of those topics, but remains wholly watchable in invoking Zombie’s characteristic style constructed from quintessential horror language in color and textures and visual subjects. This film is the only context in his career where he turns that pastiche on its head to suggest “what is sitting at the other side of this sort of stuff?”. In the cosmic sense, only more and more pain likely for the unlucky ones who have to live with it. But to at least contain it in some small realm similar to its predecessor, Halloween II has at its center a broken family unit: Deborah, Loomis, Michael, and Laurie all revolving around each other in a way that forebodes a final reunion by the great equalizer.