Y’all know me. You know how old I am (almost at my 30s! I’m dying!), how I give myself a bedtime and shit. You know if I have to watch a long-ass movie, it better get to the damn point of it all. So in the proper spirit of this post, I’d like to just get right to it: sometimes movies earn their lengthy runtime and sometimes those movies are horror movies. So I’d like to take a minute to honor 5 horror movies I deeply admire that make a unmistakable boon out of their willingness to extend themselves out in the pursuit of the creeping atmosphere that makes a horror movie work so well under your skin.

Dawn of the Dead (1978, George Romero, USA/Italy)

One of two movies on this list that has been famously subject to separate cuts: I’ve seen Dario Argento’s 119-minute European-market Zombi cut and certainly think it’s an exciting bit of zombie action on its own merit, but no masterpiece. The movie as writer/director George A. Romero finished it – 127 minutes in runtime – contains a very slow-moving and ambling middle part that Argento saw to remove and that makes sense given that I think the message Romero wanted to make out of quite possibly horror cinema’s most famous satire is American-centric: the exhausting and dead-end rise of Consumerism, the greed and selfishness it imbues in people. Of which arguably the most powerful way it gets to make that point loud and clear is letting four characters just fuck around in a mall and slowly run out of things to do and eventually run out of soul in their daily survivalism within the walls of that contemporary institution that is the shopping mall. 40 minutes where the zombies just feel like a complete afterthought and all the resources in the world cannot satisfy a small group of people’s personal qualms is the perfect usage of that additional time and a Dawn of the Dead without that is not as rich thematically.

(Better get this out of the way: most of the movies on this list are already pretty well canonized and not of the sort that demand defense given the amount of critical acclaim they’ve received [it would be take up more space to name beloved horror titles that would be close to the level of masterpiece that these films are if they weren’t too long, ie. Rosemary’s Baby and Whatever Happened to Baby Jane?]. This is once again more of an illustration of my regular rule that movies really push it with their runtimes but sometimes they actually do something with that runtime).

The Shining (1980, Stanley Kubrick, USA/UK)

The other movie on this list that famously has alternative cuts and I’ve long suspected that watching the 119-minute European cut sounded like an experience that I’d prefer to the already masterful 144-minute American cut (I confess that part of this was hearing that the European cut removes what is absolutely my least favorite shot in the movie). It certainly has more momentum, but to my great surprise, I found it was a bit less compelling as an aggravating experience watching a family collapse. Public consensus it seems has come around to figuring out that Shelly Duvall’s performance is just as essential to The Shining working as a character piece as Jack Nicholson and she’s not as favored by screentime in the European cut, but there’s also the fact that Danny Lloyd (who is not only as essential in my opinion, but he is in fact my favorite of the three central performances) losing presence as well. And anyway, I think removing a single frame of the famous Steadicam shots where Lloyd rides around in the hallways is a bigger mistake as having the skeletons shot. That hypnotic ride is pretty much representative of the movie’s power as a whole.

OK, removing it is not a BIGGER mistake, but it is almost as big.

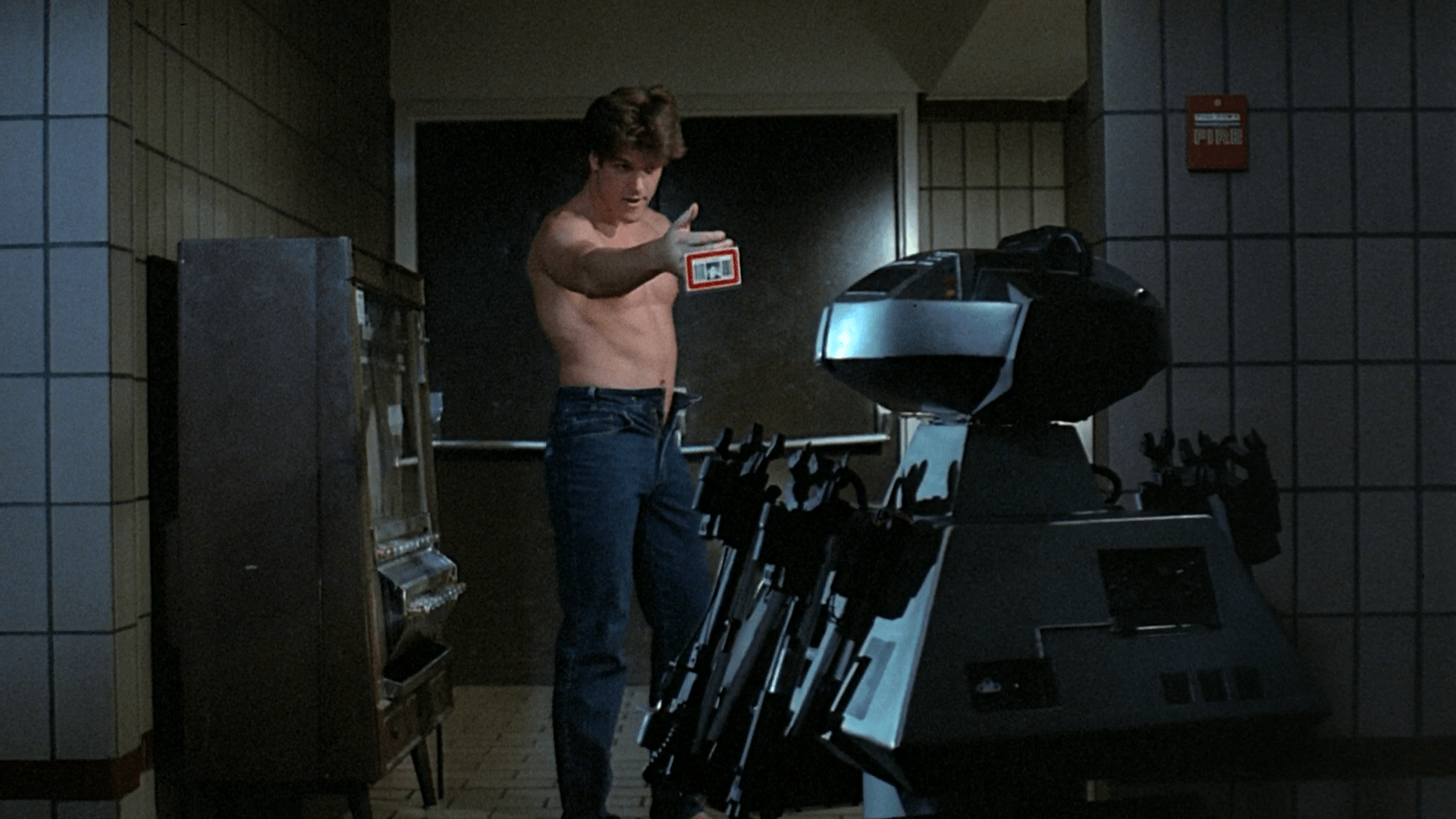

Bone Tomahawk (2015, S. Craig Zahler, USA)

The 2010s have brought some of the most unnecessarily long horror movies that I at least have seen (The Conjuring 2, It: Chapter Two, Midsommar, A Cure for Wellness, Suspiria, even the very sequel of The Shining above… Doctor Sleep). Bone Tomahawk is not the only super long horror movie of the 2010s that I love (Conjuring 2, A Cure for Wellness, and Suspiria) but it is in fact one of only two that I could say is EXACTLY the right length it needs to be (something that can not be said about the other two features Zahler has made since).

Upon giving us enough knowledge about what’s going on very early in the picture, Zahler sees to let the tensions burn up slowly and particularly off of the relationship of its central characters rather than the fact that it is a cannibal horror film. And the characters are truly the pay off of this film: it’s certainly in its interest to deliver on the expected gore effects that a cannibal film would, but those are uniformly backloaded (in fact, the actual plot basically kicks in late once we get an idea of the rhythms of the town the characters ride out of). The real interest is in giving us something of a horror movie Searchers: investigating a group of archetypal forms of masculinity slowly getting more and more fatigued and tired at their performativity, delivered by central performances and makeup that pace themselves within the generous runtime admirably.

Plus it’s just so much more unnerving to know that something horrifying is in the distance and that you’re headed right toward rather than just have it delivered to you prematurely. You need to be sunk into that harsh and empty environment before your ears start listening in on what’s wrong and intruding in that alienating isolation and once that begins, it’s a creepy enough vibe to satisfy us before the monsters come out. If that isn’t tension, I don’t know what is.

The Wailing (2016, Na Hong-jin, South Korea)

And the other 2010s horror film that is perfect in its runtime for something of an opposite reason. The Wailing is an extremely heavy horror movie, the sort that its density only reveals itself the longer it runs. For it starts as a small town police procedural, then a family drama, then layers in the demonic possession element, then starts going into the ironic Christian allegory, and before we know it all that weight crushes us just as much as the oppressively gorgeous mountainside atmosphere that this movie sets itself in. The Wailing‘s 156 minute runtime is essential to transforming this into as epic a story as horror films get and it also applies fatigue on the viewer to watch the hero keep running into false leads and twists that show he has been looking in the wrong places for answers, without ending up a bore because the desperation for the characters tightens further and further. It’s a length that is wielded with maximum power for the viewer and paced remarkably well for our investment in this ultimate possession tragedy and that results in maybe the best possession film I’ve seen yet.

The Empty Man (2020, David Prior, USA)

A movie that got hosed badly over its proper release last year that feels like it’s developing a second life in streaming akin to how some movies that don’t catch their audiences in theaters discovered their cult on DVD or VHS, The Empty Man is a wild movie that takes a lot of swings. Enough swings to be basically made up of a lot of stuff, ever changing throughout its 137 minute runtime. Which is something that, say, Luca Guadagnino’s afore-mentioned Suspiria remake gets close to accomplishing but there’s certainly one subplot in there that I think should go without any hesitation. The Empty Man certainly feels its length at points, but I can’t think of what’s the first thing I’d cut. And it’s simply hard to claim a movie is too long when it all feels like it’s in motion the way this one is, even when it feels slow at points. When you shift gears as many times as The Empty Man does without completely collapsing, it’s hard to complain about how much time you’d like to cruise on each one.

HONORABLE MENTION: It feels like cheating to invoke the name of Grindhouse in here, especially since its status as one movie or two movies is up for debate. But if you do think of it as a single movie (I don’t have an answer to if I do), know that it is a movie with my deepest endorsement for every minute of its 3+ hours as a one-of-a-kind theatrical experience.