If I had seen Strange Days sometime in my teenage years, it would have been a part of my “25 for 25” project and had some deciding factor in how I put together my personal canon and identifying the aesthetics I am attracted to most. Instead, I saw it for the first time a few months shortly AFTER I had turned 25 and it never had the opportunity to turn me into the sort of cinephile it could have, although I find it fortunate that the sort of cinephile I am happens to be very compatible with it.

I’ll make one more declarative statement before getting into the thick of what makes me a fan: If I had seen it early in my high school life, it MIGHT — MIGHT – have become my favorite movie. Indeed, it is very easy to see what it shares with my main favorite movie champion holder* Blade Runner: they’re both the stories of disgraced ex-police dealing with a case over their head set in a future version of Los Angeles while grappling with the morality behind technological advances. And I don’t think it’s a coincidence that co-writer Jay Cocks (with James Cameron, who conceived of the entire project) had previously attempted to option Phillip K. Dick’s Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? with Martin Scorsese well before it was adapted into Blade Runner.

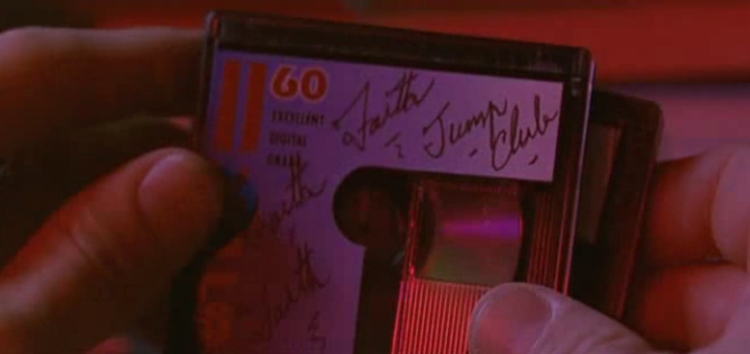

Any sci-fi film set in the future with even the slightest hint of noir owes its existence to Blade Runner anyway. Beyond that, Strange Days is a different film in every line of its DNA. Most of its differences feel rooted in the fact that Strange Days is set in 1999, which is easy to laugh aside now as an apparent lack of foresight but such if you fail to recognize that this movie was released in 1995. Cameron wanted to set the movie so close in the future that it’s practically the present, just around the corner with urgency towards its decrepit view of the future. As a result of the proximity of the time period, director Kathryn Bigelow and production designer Lilly Kilvert don’t give us flying cars and neon baths. Instead, things look like they’ve poisoned the concrete jungle into corpse-blue under Matthew F. Leonetti’s lens. The militarized police force occupy every corner, with each cut by Cameron and Howard Smith on the streets practically darting desperately to seed them. There’s an unstable paranoia that comes with being set in the turn of millennium. Even if you’re too young to remember the fears of Y2K, a character constantly refers to the imminent new year as the end of the world and it’s hard to argue when the designs feel on edge. It’s more anarchic than refined and it’s easy to see why the inhabitants of this world are eager to escape to memories of a better age with the main technology at the center of Strange Days: the SQUID, a cerebral device that is able to record an experience on a disc giving you the same physical sensations and emotions.

We’re introduced to this tech (and the movie itself) through a visceral and roughly textured single shot with the point of view of a robber before a disorienting death drop wakes up Lenny Nero (Ralph Fiennes), the aforementioned disgraced ex-cop who now makes his living selling discs on the black market as he lambasts his supplier for trying to sell him a snuff disc, because he’s got morals. As we spend more time with Lenny, we discover his pathetic and unhealthy inability to move on from his musician ex-girlfriend Faith (Juliette Lewis). Lenny uses every possible opportunity to rely on the kindness of his overworked best friend, bodyguard/chauffeur-for-hire Lornette “Mace” Mason (Angela Bassett), to find his way to clients through which to make his unsavory trade and to facilitate his stalking of Faith in whatever seedy foggy multi-colored industrial punk dives she’s performing at whenever he’s not replaying overly bright SQUID memories of her in his lonely apartment at night.

Despite the wounded sleaze (It’s very easy to see how Fiennes got this role after playing the sloppiest Nazi character ever in Schindler’s List), Fiennes communicates a sense of warmth particularly through his shocking but calming eyes seeping through his greasy long hair (something brought up by more than one character and it’s not for nothing that the movie’s first shot is a close-up of his eye**). Nero is clearly a heart-on-his-sleeve louse that is pushed around rather than pushing others around and he’s constantly able to rollback up with a salesman smile. Lenny and Mace’s dynamic, thanks to being the best performances and the center of the movie, appear to be the most honest in the film: In Lenny’s aimless appellations and intentions and Mace’s frustrated objections and straight talk out of the heart. Bassett isn’t the protagonist Strange Days eventually turns her into from the start, but she walks in already with the exhausted attitude that she’s the only one getting her shit straight and Mace as a character benefits from that attitude as she enters with one of her many moments getting Lenny out of trouble.

In any case, somebody trusts Lenny enough to arrive to him in a frazzled and anxious state asking for help: Iris (Brigitte Bako), an old friend from Lenny’s time with Faith, who drops a jack into Lenny’s car just before it’s repo’d and then disappears entirely. And whatever the reason she’s scared, Lenny is certain it has something to do with Faith’s manager/new boyfriend Philo Gant (resident 90s bad guy Michael Wincott) and a conflict of interest should be expected when you think the man your ex left you for is involved in some heinous stuff, particularly when it all circles around the impromptu murder of conscious and outspoken hip hop figure Jeriko One (Glenn Plummer), another client of Gant’s.

This is a lot of stuff, but Strange Days gets to clean it up nice because it seems like Bigelow and Cameron were intent on making two different yet harmonious movies. Cameron’s basis has always been on the emotional matrix between Mace’s feelings for Lenny while trying to protect Faith, it’s the very first element he ever conceived of the film before even the futurism (it’s for this reason that I find it very curious he gave this concept to Bigelow, who was already his ex-wife of 2 years by the start of production in 1993). And it’s a line carried through by the lead actors certainly, but Bigelow as a filmmaker appears to have little use for it. She’s making a conscious and angry film – galvanized to finally start this movie after the 1992 proved to be one of the most heated eras in American race relations – utilizing the arrangements of the characters to unlock different observations on brutality as a result of a police state, voyeurism on the sufferings of others, the self-deprecating and regressive effects of nostalgia, the ease of white men to avoid trouble that black people (and especially black women would find themselves in), the objectification of women in the media, black women being put in second rung or expected to lay down for white women, conspiracy theories, hip hop and music’s place in observing these issues and having an affect in communities, all mirroring the 1990s in which this film was released and the anxiety in the air. Surrounding these characters’ romantic complications is a whole society developing and decaying in ways that were apparent in the real world. The resultant world-building feels like an extension of the heightened emotions of their romantic complication and lack of awareness.

I’ve already gone through the production design insisting that police are ever-present, down to helicopter lights constantly flashing through the windows. But it’s also in the manner that, for a 2 1/2 hour movie, Bigelow’s direction is violently fast and may as well prove to be coming off her growth as a notoriously “masculine” director with Near Dark and Point Break. There are few action setpieces in Strange Days and they are dangerous and fantastic (while also being the areas where Mace takes charge), but even the majority dialogue sequences have Leonetti’s camera movements whipping around like a paranoid eye and Smith and Cameron’s cutting turning the atmosphere frazzled, denying any sense of calm. And Bigelow is unafraid to go to harrowing places: halfway through the film comes a controversial rape/murder sequence involving cross-cutting with a character witnessing it via the SQUID, first with gleeful interest as he misreads the scene and then with horror as he recognizes the victim, her emotions, and the actions. The end result indicts an audience’s interest in the exploitation of individuals for profit and entertainment.

I am making this movie sound a lot more unpleasant than I feel it is: it is paranoid, it is violent, it is charged, but it has two lead performances able to guide us and make us feel safe even when they don’t and it has moments of relief from the tension that appears throughout the movie [particularly scenes involving Mace’s family and particularly her son Zander (Brandon Hammond) who has a small but comforting slow-motion shot involving fireworks to assuage Mace’s fears]. I also feel like I am making this movie sound perfect, which is not even close to. For one thing, while Strange Days is ahead of its time in many ways, it’s not altogether prophetic. Being a 1995 film about the future that doesn’t invoke the internet at all makes it an outlier and not in a good way. It also has a mostly unimpressive supporting cast beyond Fiennes and Bassett: Lewis feels like the weak link in the movie’s core conflict, feeling way too young for the jaded rock star part she’s trying to play and treating her character’s contempt for Nero less as genuine frustration of a man who is essentially stalking her and more like a teenager lying because she feels like it. Even if that’s how the character is meant to be (which I don’t think so – I like to think Faith does not want Nero to get hurt but she genuinely does not have any remaining romantic feelings for him), it feels like it makes the emotions so much flatter. Meanwhile, the best the supporting cast can do is play unidimensional archetypes of roles they seemed to be typed as in the 1990s like Vincent D’Onofrio being one note of angry or Tom Sizemore being one tone of grimy.

And yet still, I love Strange Days with all its future warts and if there’s something I think signifies how easily I am able to forgive its sleights, it is its climactic finale during a boisterous New Millennium party in the streets. At one point, it is the most harrowing sequence in the film as someone is beaten to the ground in closeness, the next the crowd has jumped in to save a life and it’s a release of all the pent-up anger the film has built under itself, and finally Bigelow inconsistently decides that all is right: justice is served by a confused system that nearly killed an innocent minutes ago and the world does not end at midnight like we feared. And while this is an ending I fundamentally disagree with, the final grace note of where our characters end feels so emotionally right and reassuring as the streets celebrate all around them and we look up to a new night sky while Lori Carson & composer Graeme Revell fades into Deep Forest in a peaceful compulsively delightful ending.

And then the disc ends and I open my eyes.

*give or take a Casablanca.

**In fact, that’s another thing Strange Days and Blade Runner have in common: a close-up of a character’s eye appears within the opening cuts of each film.